The Philosophy Behind Hierarchy Budget

Your Budget Is a Psychological Document

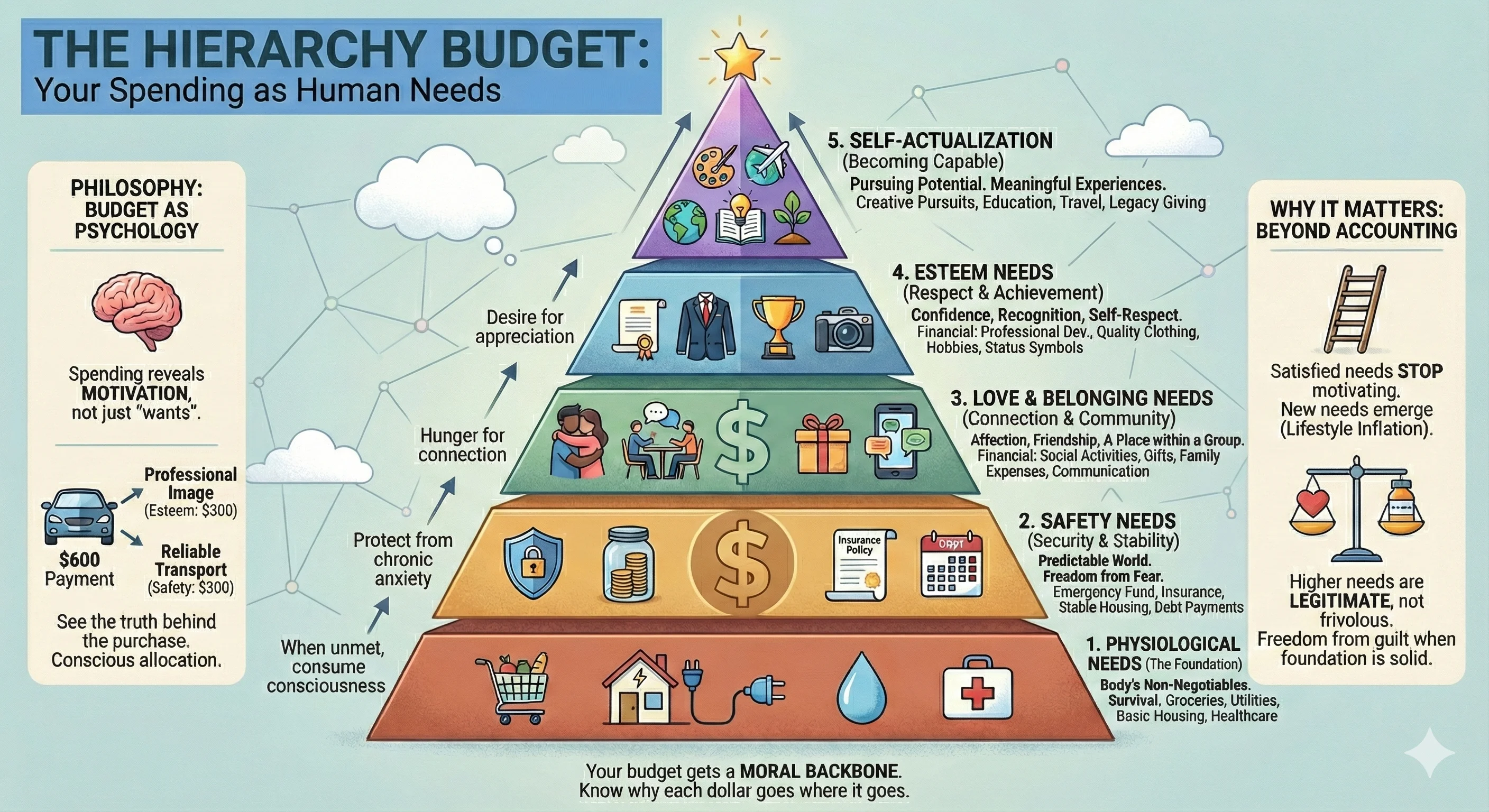

Every dollar you spend reveals what you’re motivated to fulfill. Not what you think you want. What you’re actually trying to get.

As Maslow observed:

“The average desires that we have in daily life…are usually means to an end rather than ends in themselves.”[^1]

You don’t want money. You want safety, or status, or belonging.

You don’t want a car. You want reliable transportation (physiological/safety), or professional credibility (esteem), or the feeling of not being inferior to your neighbors (esteem).

You don’t want the restaurant meal. You want connection with friends (love), or relief from cooking (physiological), or to be seen as someone who goes to nice places (esteem).

The purchase is the means. The need is the end.

Traditional budgeting categorizes by accounting logic: fixed vs. variable, essential vs. discretionary, debt vs. savings. These categories obscure what’s actually happening. They can’t tell you whether your $600 car payment is meeting a need for reliable transportation or financing a status symbol.

The Maslow framework cuts through this by organizing spending around what human needs are actually being served.

When you see that your car payment splits into $200 for transportation and $400 for status, you’re seeing the truth. And once you see the truth, you can choose differently.

The Hierarchy of Human Needs

Maslow discovered that human needs arrange themselves in a hierarchy of prepotency - lower needs tend to dominate when unsatisfied.

1. Physiological Needs

Food, water, shelter, sleep, health. The body’s non-negotiables.

When these go unmet, they consume consciousness entirely. As Maslow wrote:

“For the man who is extremely and dangerously hungry, no other interests exist but food.”[^2]

This isn’t metaphor. When your budget is consumed by physiological needs, your cognitive capacity shrinks. You have less mental energy for planning, for impulse control, for strategic thinking. Scarcity at this level makes it harder to think your way out of scarcity.

Financial expression: Groceries, utilities, basic housing, healthcare

2. Safety Needs

Security, stability, freedom from fear. The desire for a predictable world where unexpected dangers don’t threaten survival.

Financial expression: Emergency fund, insurance, stable housing, debt payments, retirement savings

3. Love & Belonging Needs

Affection, friendship, community. The hunger for connection and a place within a group.

Maslow noted:

“The thwarting of these needs is the most commonly found core in cases of maladjustment.”[^3]

Financial expression: Social activities, gifts, family expenses, communication services

4. Esteem Needs

Self-respect, achievement, recognition. The desire for confidence and appreciation from others.

When thwarted, we feel inferior, weak, helpless.

Financial expression: Professional development, quality clothing, personal appearance, hobbies, status symbols

5. Self-Actualization

Becoming what you’re capable of becoming.

“A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately happy. What a man can be, he must be.”[^4]

Financial expression: Creative pursuits, education, travel, meaningful experiences, legacy giving

Why This Matters for Your Budget

Satisfied Needs Stop Motivating - New Needs Emerge

Maslow’s critical insight:

“A satisfied need is not a motivator.”[^5]

Once you have stable housing and enough food, physiological needs stop driving behavior. But new needs emerge to take their place:

“Man is a wanting animal and rarely reaches a state of complete satisfaction except for a short time. As one desire is satisfied, another one pops up to take its place.”[^6]

This is the mechanism behind lifestyle inflation. When you earn more and satisfy lower needs, you don’t feel satisfied - you feel new needs awaken. The person making $40K struggling with safety needs and the person making $400K struggling with esteem needs both feel equally broke.

Each satisfied level unlocks the next level of need, which feels just as urgent as the previous one.

Without a framework that shows you this pattern, you get swept along indefinitely. The Maslow hierarchy gives your budget a structure - a way to see what’s happening and choose consciously.

Partial Satisfaction Across Levels

Maslow observed:

“The average member of our society is most often partially satisfied and partially unsatisfied in all of his wants.”[^7]

He illustrated with specific percentages:

- 85% satisfied in physiological needs

- 70% in safety needs

- 50% in love needs

- 40% in self-esteem needs

- 10% in self-actualization needs

You’re not stuck at one level. You’re working across all five simultaneously, with different degrees of satisfaction at each.

Your budget should show this. The hierarchy visualization reveals how much attention each level is getting relative to what you’ve allocated for it.

The Whole Person Budgets

Maslow insisted:

“The individual is an integrated, organized whole.”[^8]

When you’re anxious about safety (unstable job, no emergency fund), it affects everything: sleep, relationships, ability to think long-term.

Your budget impacts your entire life. Chronic financial stress keeps you stuck at lower levels. Money allocated to safety provides psychological calm. Investing in self-actualization when basics aren’t met creates guilt and anxiety.

Freedom From Guilt

Traditional budgeting treats higher-level spending - esteem, self-actualization, even love and belonging - as optional “wants” that responsible people minimize. This creates constant guilt.

The Maslow framework reveals something different: these are legitimate human needs, not frivolous wants.

Maslow asked directly:

“Who is to say that a lack of love is less important than a lack of vitamins?”[^9]

He observed that when higher needs emerge:

“The organism may equally well be wholly dominated by them.”[^10]

A person with unmet esteem needs can be as consumed by that deficit as a hungry person is consumed by hunger.

When your hierarchy shows that physiological and safety needs are properly funded, and higher spending is proportionate to your income, that’s not irresponsibility. That’s being human.

You can spend on connection, growth, and confidence without the nagging voice saying you’re doing something wrong.

The framework gives you permission to meet higher needs when they’re in balance - because you can see clearly that you’re not neglecting your foundation.

Wants vs. Needs

Your budget is not a failure of discipline. It’s a reflection of what you’re motivated to do.

When you organize spending around human needs instead of accounting categories, you see exactly what your money is serving. Which needs are demanding resources. Which are neglected. Where you have choice vs. where you’re constrained.

Maslow provides the answer to “What is a want and what is a need?”:

- Physiological needs are non-negotiable

- Safety needs protect you from chronic anxiety

- Love needs are about real connection

- Esteem needs build genuine confidence

- Self-actualization is becoming what you’re capable of

But there’s personal discretion within each level.

That $600 car payment? Split it honestly. Maybe $300 is reliable transportation (physiological/safety). Maybe $200 is necessary professional image (esteem). Maybe $100 is about status (esteem). Or maybe all $600 serves safety because you genuinely believe that specific car is necessary.

Split it according to what you actually believe is necessary. Once you see it clearly, you can ask: are these allocations serving what I actually value?

When you allocate consciously, your budget gets a moral backbone. You know why each dollar goes where it goes. You can see whether those allocations serve what matters to you - or whether you’re spending on autopilot, driven by needs you haven’t acknowledged.

Common Misconceptions About Maslow’s Hierarchy

The popular understanding of Maslow’s hierarchy often misrepresents what he actually wrote. Here’s what he really said:

It’s Not a Ladder You Climb

Maslow never said you complete one level before moving to the next. He explicitly stated in his original 1943 paper: “most members of our society who are normal, are partially satisfied in all their basic needs and partially unsatisfied in all their basic needs at the same time.”

You’re not “stuck” at one level - you’re working across all five simultaneously, just with different degrees of satisfaction at each.

Higher Needs Aren’t Less Important

When a higher need is calling, it can dominate your consciousness just as completely as hunger dominates a starving person. Maslow wrote that when higher needs emerge, “The organism may equally well be wholly dominated by them.”

The person desperate for respect, connection, or meaning isn’t experiencing a “lesser” need - they’re experiencing a different but equally powerful human drive.

It’s Descriptive, Not Prescriptive

Maslow was describing what he observed about human motivation, not prescribing an ideal path. The hierarchy shows how needs tend to emerge, not how they “should” be pursued. He documented numerous exceptions: creative people who create despite lacking basic needs, people who reverse esteem and love, those who permanently lose higher needs due to chronic deprivation.

Pre-potency Means “Tends to Come First,” Not “More Important”

When Maslow says physiological needs are “pre-potent,” he means they tend to emerge first and, when severely threatened, can overshadow other needs. But once reasonably satisfied (not perfectly satisfied), other needs emerge with equal force.

This is why the wealthy person struggling with meaning or the secure person craving connection feels just as broke as the person struggling with rent.

About This Tool

Hierarchy Budget applies Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs theory to personal finance. This tool is not affiliated with or endorsed by the Maslow estate. All theories and concepts referenced are based on Maslow’s published academic works, which are cited below.

References

[^1]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

[^2]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

[^3]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

[^4]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

[^5]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

[^6]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “Preface to Motivation Theory.” Psychosomatic Medicine, 5(1), 85-92.

[^7]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

[^8]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

[^9]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

[^10]: Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

Related Pages

- Getting Started - Create your first budget

- Interpretation Guide - Understand your patterns

- Monthly Budget - Start budgeting

- Dashboard - View your hierarchy